"India is now a top five country, and we'll probably climb further"

Indian people are playing, says Dhruva's Rajesh Rao, but the road to payment might be long, and unforgiving for the country's indie developers

Even the most cursory analysis of the Indian games business reveals the vast gulf between potential and reality.

India's promise can be encapsulated, swiftly and powerfully, by a single, very large number: 1.25 billion, the country's population. The problems that stand in the way of even half that number becoming a smartphone owning, in-app purchasing target audience for game developers are complex and interconnected, demanding a variety of solutions that will play out over very different timescales. Nazara Technologies sees a mature Indian games market as a five-year bet. Moonfrog Labs has suggested ten.

"The historical data shows that we love free, and we take a little time"

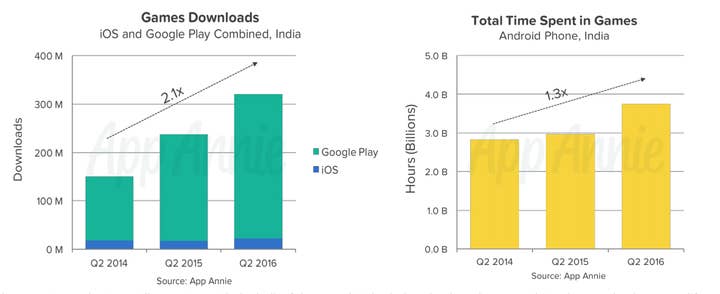

For Rajesh Rao, the chair of the Nasscom Gaming Forum and founder of Dhruva Interactive, which was acquired last year by Starbreeze, it is at least possible to see the founding stones on which the Indian games business will be built. According to a specially commissioned App Annie report, officially unveiled at Nasscom GDC last year, India entered the top five countries for combined iOS and Google Play game downloads for the first time in Q2 2016 - jumping two places in the space of a year to nestle behind Russia, Brazil, China and the US.

With 1.6 billion downloads accrued for the whole of 2016, Rao believes that one of the great questions over the potential of the Indian market has been answered.

"The proof is in the downloads growing," he says when we meet at Nasscom GDC. "1.6 billion downloads has happened. That's not notional. India is now a top five country, and we'll probably climb further. Based on what the CAGR is showing, we could go into the top three.

"Whether people are playing is no longer a debate. Now it's a matter of how many people will pay. That's the debate."

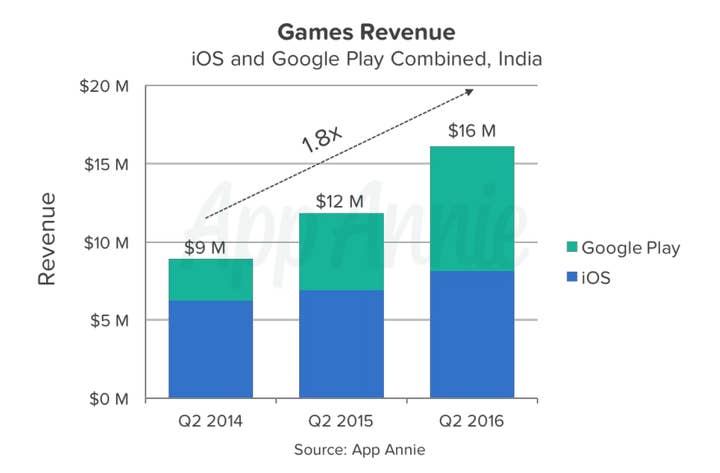

App Annie's data indicates that Indian people will continue to play, and in ever increasing numbers. The 1.6 billion downloads amassed last year is projected to reach 5.3 billion by 2020; in that same timeframe, Statista forecasts that the number of smartphone users in India will rise from 292 million to 444 million. These are huge numbers, suggestive of a huge and valuable market, but this is the point at which the gulf between potential and reality becomes startlingly apparent. In the same quarter that India placed fifth in the world for iOS and Android game downloads, App Annie's data shows total revenue of just $16 million. Two years before, in Q4 2014, total revenue was $9 million.

According to App Annie, that is on the cusp of rapid change. A CAGR of 87% will push the Indian mobile games market to $1.1 billion in annual revenue by 2020; a vast improvement over the value of the market today, and the kind of figure that would draw the gaze of many international companies. When I mention App Annie's projection to Rao, though, his response is notably measured.

"When we saw that, our view was... it seemed like a fairly aggressive extrapolation," Rao says. "Getting people to pay is a change in mindset. It has to come from themselves. You can create things that help to accelerate it, but you cannot force them."

"Whether people are playing is no longer a debate. Now it's a matter of how many people will pay. That's the debate"

To that end, there are "enablers" being developed and implemented to hasten that transition: faster, cheaper and more pervasive wireless internet, which both Google and Facebook are actively pushing; mobile wallets, carrier billing, and a broader range of payment options; lower payment thresholds on the mobile app stores, after the minimum price tier on Google Play (by far the most popular store) dropped from Rs. 50 to Rs. 10 (about 15 cents).

However, Rao is quick to point out that there is no "magic bullet" for India. He would like to see a further reduction in the minimum app store price tier, for example; RS. 5 or Rs. 2, which would make payment more feasible and attractive for millions of people. Rao describes the issue of payment in terms of India's "cultural" past rather than simply about infrastructure. "Carrier billing is not a magic pill," he says, referring to one of enablers mentioned in App Annie's report. "It will definitely show results, but it's not the only thing holding us back."

But culture's change, and Rao believes the maturation of the Indian film market is indicative of what lies ahead for games. The price of a cinema ticket was "between Rs. 5 and Rs. 25 for a very long time," but an improvements to the product over the last ten years - in the form of modern theatres, and films with better production values - has convinced the growing middle-class that the experience has a higher value. "Now you could have a Friday show for 500 rupees," Rao says. "And nobody's blinking."

The same effect can be seen with television, which at one point was operated by the state. According to Rao, the first private channels were introduced in the early 90s, all of them funded by advertising. Then channels were offered for subscription through cable operators, in bundles or individually. "This channel is Rs. 5 per month, that channel is Rs. 7 per month," he continues. "Cut to now, 15 or 20 years later, some channels are priced at Rs. 150 per month.

"The point is that, eventually, [Indian people] will pay for game content. But the historical data shows that we love free, and we take a little time."

"A lot of these guys are going to do a lot of soul-searching at some point, about how they can really survive"

If Rao is correct, this poses a significant problem for the country's community of developers, most of whom are in small teams, with limited access to funding, and far from the radar of international publishers. These factors make the Indian iOS and Android storefronts the most accessible place to do business, but there isn't much revenue to go around.

For Rao, the lack of experience within the Indian startup scene - unavoidable given the relative age of the country's games industry - is preventing developers from making choices that the situation demands. Choices made from passion, rather than the reality of building a business and the pragmatic necessity of survival.

"I think there's a lot of developers who just jump in without thinking," he says. "The developer community in India, the characteristic that distinguishes it from the community in the West, is that the startups there are more often than not people who have worked in large companies; they've put in their years, they have experience. Then, after that, they're stepping out into startups."

India's developer community is young, Rao says, with much lower overheads than in more developed industries around the world. "They can make their runway last for quite a while. But, eventually, if you aren't making money... The reality is that a lot of these guys are going to do a lot of soul-searching at some point, about how they can really survive.

"This notion of indie, and doing my own game, making the games I like to make - all nonsense, because that doesn't feed you. A lot of the guys got caught up in that kind of thinking, and it's all fine and dandy, but where is the money?"

"If you don't have a successful business model, then at some point you come to the end of your runway."

Rao offers Timuz as an example of the kind of developer that India needs. Founded in Hyderabad by Ahmed Mohammed, Timuz has grown from 4 people to more than 100 in just six years. It produces games on a very busy release schedule, spanning multiple genres, steadily building a large enough audience to monetise through interstitial advertising. The company's biggest game to date is Train Simulator 2016, but Timuz is thriving on the strength of a portfolio rather than any one product.

"That guy is killing it," Rao says. "He's making a ton of money, from what I know. That means he's cracked something. He understood that Indians are not paying yet, so he's building a portfolio.... Good man. More power to you. In doing so, he has a library of content in enough genres and enough styles that he now has data that can help him in his future.

"Smart. That's a smart indie."

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner for Nasscom GDC. Our travel and accommodation costs were provided by the organiser.