Critical Consensus: The Witness is tough, uncompromising, triumphant

Jon Blow's second game is a visionary work, but one at odds with the expectations of modern players

It says a lot about Jonathan Blow that the money he earned from Braid could have funded a few lifetimes worth of idle comfort, and yet he spent virtually every cent on making his next game. Indeed, the money earned from Braid - widely credited as the game that catalysed the resurgence of indie development - could have funded a series of projects on a similar scale, and yet he spent virtually every cent on making just one. This one, The Witness, developed over a period of almost seven years, and as close to a make-or-break artistic statement as the games industry has ever produced.

For these reasons and more besides, the critics have been waiting impatiently for The Witness to arrive. For many of them, Braid will have been a seminal moment: an early glimpse of what a digital service like Xbox Live could mean for the variety and diversity of the games we play, and proof of what was possible when a fearsomely dedicated individual was free to express their talent.

"The Witness' scope and production values are the equal of many a big-budget, big-publisher release"

Eurogamer

For others - the minority, it should be noted - Braid was a digital manifestation of its creator's pretensions, grasping for profundity and coming up with a nothing more than a neatly designed puzzle game. I was reviewing games back in 2008, and Braid was the middle point of a banal sequence of releases between Army of Two and Star Wars: The Force Unleashed. I ached for a game with pretensions of any kind, in any direction. I can recall my sense of bemusement at the dismissive reaction even now.

All of which is to say that The Witness arrives with far more baggage than independent games are generally expected to carry, the moment when one or the other view of Braid and its creator can finally be confirmed in the minds of the critics. Based on the reviews currently available - and there are many - all of those years and millions of dollars were not invested in vain. The Witness was notable for being among the most anticipated games of 2016, and it will likely finish the year as one of the very best.

According to Eurogamer, which gave The Witness an admiring recommendation, all of that time and effort and money is right there on the screen, both on the surface and in the content. It took Eurogamer's reviewer 23 hours to solve 365 of the game's puzzles, which is a little over half of the amount Blow says are scattered across its island landscape. And that landscape is an impressive sight.

"Although it has a certain cool minimalism in its presentation - there's no music, and the island is a deliberately hushed and lifeless place - The Witness is a quite gorgeous example of the 3D modeller's art, characterised by washes of rich, soothing pastel colour and a sculptural attention to detail. The island is as sunnily inviting, as reach-out-and-touch tactile, as it is eerie and remote.

To put it another way, The Witness' scope and production values are the equal of many a big-budget, big-publisher release, and its substance would shame most of them... I'm not in the habit of discussing value for money in game reviews - it's too much of an eye-of-the-beholder issue - but I hope that answers the worries of those who were surprised by its premium price point."

"Surely it can't be that simple. It is... Mechanically speaking: The Witness is maze puzzles. Full stop"

Polygon

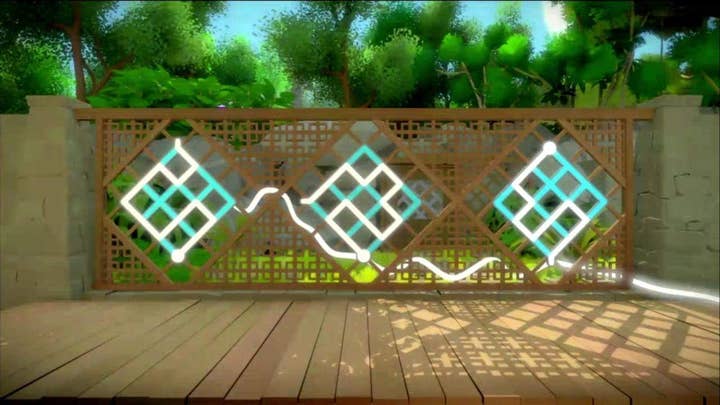

That expertly realised surface is one of the ways in which The Witness rewards the player, Eurogamer says, but it is certainly not the only one. The real meat of the experience is in the hundreds of puzzles to be discovered, some of them relatively simple, some astoundingly difficult, all of them mazes solved by tracing a line between an entrance and an exit without crossing itself. In Polygon's review, the critic notes the assumption made by his colleagues that those puzzles must be united by a "hook" or a "twist."

"The assumption is that a simple sequence of hundreds of maze puzzles can't be the next project from the creator of Braid, a game in which narrative was so essential that it was inextricable from the mechanics. Surely it can't be that simple. It is... Mechanically speaking: The Witness is maze puzzles. Full stop."

But Polygon's critic also acknowledges how "reductionist" that assessment might sound on first hearing. Yes, the vast majority of what you'll be doing in The Witness is solving puzzles, but the way Blow approaches educating and empowering the player is both singular and brilliantly effective.

"What makes The Witness interesting is not solely the solving of puzzles, it's the way in which the player must discover what I've come to think of as 'the puzzle vocabulary.' Every puzzle is a maze, but most mazes have multiple paths, and to find the correct one, you must understand what the symbols scattered throughout the mazes mean.

"When I asked co-workers for help with solving a couple of late puzzles (sorry, I was weak) it took just as much time for me to explain the rules of what I was doing as it did for them to solve it. My analogy of a 'puzzle vocabulary' was more apt than I initially realized. The information I held in my head about puzzles in The Witness was literally better expressed via signs and symbols and experience than it was via English. It's all done without a single written word of instruction."

Blow interrogated how games convey meaning in Braid, and The Witness further explores the subject by rejecting so many of the tricks and tools and tutorials on which game designers have come to rely. In that sense, it is possible to admire The Witness for its ambition and commitment even when that approach can lead to feelings of frustration and - in the case of a handful of reviewers - alienation. Wired's critic seems to belong to this conflicted camp, concluding that The Witness only gives the impression of meaning anything at all.

"By refusing to offer any guidance at all, The Witness runs the risk of players bouncing off it entirely. I'm not sure it cares"

Wired

"The only answer you're likely to get," the reviewer states, "is the one you make yourself.

"This is The Witness: A set of circuit puzzles on a ruined, abandoned island. The puzzles are stretched across the landscape, with different locations revolving around different sorts of puzzles, each adding a different rule to the basic circuit-completion idea. By traveling to different parts of the island, you come to understand different rules, then return to apply those rules to more complex puzzles you couldn't solve before, eventually opening new paths, activating mysterious machines, and figuring out what in God's name is going on here.

"I think that's what you're supposed to do. To tell you the truth, I'm less than confident. I've sunk hours upon hours into The Witness. I feel like I might be halfway through it. But I have no idea what's going on. The circuit puzzles stubbornly refuse to explain themselves; understanding the rules governing them is a matter of trial and error (and error and error), piecing together functional heuristics by inference and work. Likewise, there are no signposts explaining anything about the game's setting or narrative impetus. I don't even know who I am.

"I'm on an island, and it's lovely and intricate but I don't know why I should care... By refusing to offer any guidance at all, The Witness runs the risk of players bouncing off it entirely. I'm not sure it cares."

If Wired's reviewer does not regard himself as smart enough for Blow's puzzles, he is certainly smart enough to frame it as a "fundamentally subjective" observation, one that won't be a problem for everybody. The counterpoint can be found in another venerable organ, Time Magazine, which awards The Witness full marks at the climax of a truly gushing review. Both Wired and Time regard draw comparisons to the classic 1993 game, Myst, and yet their experiences are a reminder of just how much games can resist objective assessment.

"Who created these puzzles? What does solving them mean? And where exactly are you, anyway? I'm going to rain check theories to avoid spoilers, but I can say searching for those answers had me pulling science and philosophy books off my shelves. I've had to look up obscure Renaissance thinkers, arthouse filmmakers and unicursal puzzle mechanics... The important thing is that The Witness never asks you to go to such lengths. Its epiphanies are motivation enough.

"The game's breakthrough idea is how all of these puzzles intersect, subliminally delivering information payloads without uttering a word. It's a literally consciousness-expanding process, a way of teaching you to teach yourself. The game's concepts accrete and eventually coalesce into rivers of awareness. The Witness makes you feel smart because you are being smart... There's no design flimflam here."

"It's a literally consciousness-expanding process, a way of teaching you to teach yourself"

Time

Time's review is one of many to award The Witness a perfect or near-perfect score, but one can easily imagine all of the well intentioned rhapsodising about "rivers of awareness" as a potential deterrent. Not every game should be for everybody of course, but even in reviews that seem awestruck by its singular brilliance, the notion that The Witness actually overshoots its high-level goals comes up again and again.

Polygon credits Blow with achieving things that perhaps no other game designer ever has, and yet the score is an 8 out of 10. "I have no idea how people who have solutions a click away are going to avoid that temptation but, more damningly, The Witness doesn't seem to know either," the reviewer says. "The game makes no concessions to the fact that it's being released in 2016, an era in which a full list of all the solutions will be available within 24 hours of release. It simply trusts the player not to cheat. That trust would be a lot less tempting to violate if The Witness weren't such a mean piece of shit from time to time."

Eurogamer, too, praises the "amazing clarity" of the game's design, and yet there is a higher accolade than "Recommended" that The Witness didn't quite justify. For a game of such substance, the reviewer says, there is something hollow in the larger mystery of the island, hinted at in crumbling statues and scattered audio tapes. In this way, The Witness can seem, "self-involved and wilfully obscure, carrying the whiff of alternate reality games: a riddle to be crowdsourced rather than a message to be understood.

"Blow needn't have tried to make a puzzle out of art when he had already, so beautifully and so successfully, made art out of puzzles."