Brazil Game Show: This is one market that Xbox One can win

Wild inequality in console prices highlights the difference in Microsoft and Sony's commitment to Brazil

This year's World Cup was widely praised as one of the finest in the tournament's long history, a celebration of the people's game in the country that had become its spiritual home: Brazil.

And yet the months leading up to that first game were anything but joyful. In February, a 9 per cent rise in bus fares in Brazil's biggest cities sparked an extended period of protest, rioting and civil unrest. From an outsider's perspective, the actual difference in the price of a ticket would appear negligible, but for many Brazilians it was just one more example of the big-spending government's apparent disregard for its own people. Public services were severely underfunded. The prices of desirable products astronomically high.

In terms of minutes worked to obtain a ticket, that bus ride cost the residents of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro almost double the amount paid by someone in New York City or Paris. With foreign goods - which are subject to a labyrinthine tangle of import taxes, fees and charges - the situation occasionally beggars belief. In September 2013, for example, The Economist's Big Mac Index put Brazilian burgers behind only, "three much richer countries, (Norway, Sweden, Switzerland) and one dysfunctional one (Venezuela)."

"The Xbox One launched at a suggested retail price of R$2200, cheaper than Sony's console by more than 700 US Dollars"

Brazil has come a long way in the last decade. The country's middle-class grew by 40 million people between 2003 and 2011, and GDP per capita tripled in the same timeframe. A growing number of Brazilians now aspire to a similar lifestyle to that enjoyed in regions like North America and Europe. Cars, consumer gadgets, games consoles; these items are more highly prized in Brazil than ever before, and yet the government's protectionist tax policies are keeping them beyond the reach of even those in the new middle class.

Not that you'd know it from visiting the Brazil Game Show. The PlayStation 4 was released in Brazil at the same time as the whole of Europe, and several months ahead of Japan. For Microsoft, Brazil was one of just 13 countries chosen for the Xbox One's global launch day. Last generation, the situation was very different - Xbox 360 took a year to reach the market, the PlayStation 3 took nearly four - but this time Brazil was treated as an equal to the world's most established console gaming markets. The BGS showfloor tells a similar story, awash with huge stands for Destiny, Borderlands, FIFA and Call of Duty.

In reality, the Brazilian gaming scene is dominated by digital platforms: mobile, social networks, PC downloads and free-to-play MMOs, which were accessible and affordable enough to allow gaming to thrive. SuperData puts the size of the digital games market in Latin America at $4.5 billion in annual revenue, with Brazil responsible for 35 per cent of that amount. Consoles and console games, on the other hand, are a small piece of that much larger picture. Exactly how small is difficult to define, but it's evident that the spectacle of BGS is as much about desire as it is reality.

"There's so much passion involved that people try to arrive at 5am," says Marcelo Tavares, the organiser of a show that has grown exponentially since I last visited in 2012, when League of Legends was the most popular game by a wide margin.

"We try to tell them that it isn't the time the show opens, but they say, 'No, we're coming at 5am.' It's different in other countries. I went to Gamescom and I saw most visitors arriving on time, not five or six hours before. That used to be a big surprise, but now we know it's going to happen every year. We're always trying to make it better for them."

And console companies should be following that example. When the last generation started in late 2005 Brazil was a very different place in terms of its economic standing, and it seems likely that it will be even more different by the time the Xbox One and the PlayStation 4 become obsolete. Even before they selected Brazil as a first-run launch country, both Sony and Microsoft showed recognition for that bright future by embracing a costly but highly effective way of navigating its convoluted tax system to arrive at a more sensible price for the consumer: manufacturing consoles within the country.

Granted, Microsoft took that step more than 18 months ahead of Sony, just as it had launched the Xbox 360 several years ahead of the PlayStation 3, but ultimately the price of both consoles came crashing down by as much as 50 per cent. For Brazilian gamers, many of whom had never been able to afford a console through legitimate channels, it seemed like a positive and irreversible step.

"In the most rudimentary terms, it's a case of putting dollars in to get dollars out, and Sony has elected to withhold that investment for now"

As it turns out, only Microsoft has made good on that commitment for the new generation of consoles. In a report published in March this year, Bloomberg named Brazil as the most expensive country in the world to buy a PlayStation 4, its suggested retail price of 3999 Reals (R$) putting it ahead of second-place Argentina by more than $300, and ahead of third-place Sweden by more than $1000. To put that figure in its proper context, the Xbox One launched at a suggested retail price of R$2200, cheaper than Sony's console by more than $700 at the current exchange rate. It should be noted that both consoles were available at the Brazil Game Show from the retailer Saraiva for substantially lower prices, but that yawning chasm remained: an Xbox One without Kinect was R$1599, a PlayStation 4 was R$2499.

When I meet with Ken Balough, the director of marketing and communications for PlayStation in Latin America, he is full of enthusiasm for what the simultaneous launch of the PlayStation 4 says about Sony's belief in the Brazilian market. "It's a reflection of how Sony sees Latin America as a whole. When it came time to launch the PlayStation 4 we were cognisant of the fact that we wanted to launch it in Latin America at the same time. We did United States, and within two weeks we'd done Europe and the whole of Latin America. That's exactly how we see the market. It needed the simultaneous launch that it had never had before. It shows the commitment we have to this region."

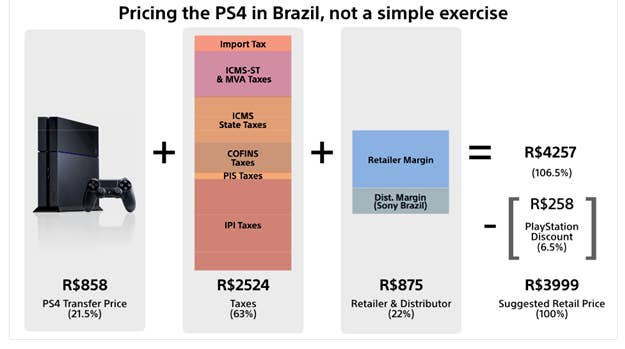

However, those words ring hollow when one considers the price. Any company taking the Brazilian market seriously must necessarily acknowledge that it is unique even within Latin America - both in the obstacles it presents to international businesses, and the financial rewards it could offer in return. When Sony announced the PlayStation 4's pricing for the region it went to great lengths to highlight the costs of bringing a console to market in Brazil, releasing an illustrative flow-chart accompanied by reassurances like, "We are doing everything possible at this moment to reduce the PS4 price for you."

In truth, though, the far lower price of the Xbox One suggests that bringing that price down further - a lot further - is certainly not beyond Sony's capabilities. In the most rudimentary terms, it's a case of putting dollars in to get dollars out, and Sony has elected to withhold that investment for now, even as it claims to hold the Brazilian market in similar esteem to its strongholds elsewhere in the world. This contradiction is not lost on gamers in the country, as the disgruntled comments below the official announcement of the PlayStation 4's price clearly indicate.

Of course, every company has priorities, and those priorities are influenced in no small part by financial stability. Taking into account the full breadth of both companies, Sony has fewer resources at its disposal than Microsoft to develop its business in countries like Brazil. But it's difficult to escape the notion that PlayStation has consciously ceded the market to Xbox here, allowing the goodwill it built when the PS2 was Brazil's dominant console to slowly ebb away. According to data from Gfk - published here and here - by the start of 2013 the Xbox 360 had an 85 per cent market share for that generation, with the PlayStation 3 and the Wii left to divide the remaining 15 per cent.

"It's difficult to escape the notion that PlayStation has consciously ceded the market to Xbox, allowing goodwill to slowly drain away"

As I meet with publishers, developers and gamers over three days at the Brazil Game Show I am constantly reminded that there has been a market for console gaming in the country for far longer than the global industry has shown a commercial interest. Historically, that grassroots enthusiasm largely played out in the black and grey markets, potential customers blocked from legitimate commerce by low wages and high prices. But even now, after per capita income has climbed every year for more than a decade, it is still necessary for the console companies to play their part, to make the sort of investment in Brazil that will allow a legal market to thrive.

This year, the Brazil Game Show had a very special guest, the second most requested industry figure based on an exit poll from last year's show: Ed Boon, the creator of Mortal Kombat, a series that rose to prominence at a time when the games industry barely even acknowledged a country like Brazil. And that, Marcelo Tavares tells me, is entirely the point.

"In the past we had piracy and games being imported unofficially," he says. "Even then, fighting games like Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat were the most popular. Ed Boon did a talk show on TV yesterday, the most important talk show in the country, and that's because they asked for him. They wanted Ed Boon on the show. He's probably more famous here than anywhere in the world.

"[International] companies should be paying attention to this market. They should come here to research the market and try to understand the passion of the Brazilians. If they have their games in Portuguese, if they have their games at a good price, they will succeed here."