Ubisoft Montreal: "We invent when we need to invent"

VP of creative Lionel Raynaud addresses the similarities in Ubisoft's AAA franchises

If you were one of the four million or so people who bought Ubisoft's Watch Dogs when it launched last month, you may have felt a nagging sense of déjà vu. Not to Grand Theft Auto necessarily, that grand old man of the urban open-world, but to other games in Ubisoft's portfolio, and often in unexpected ways.

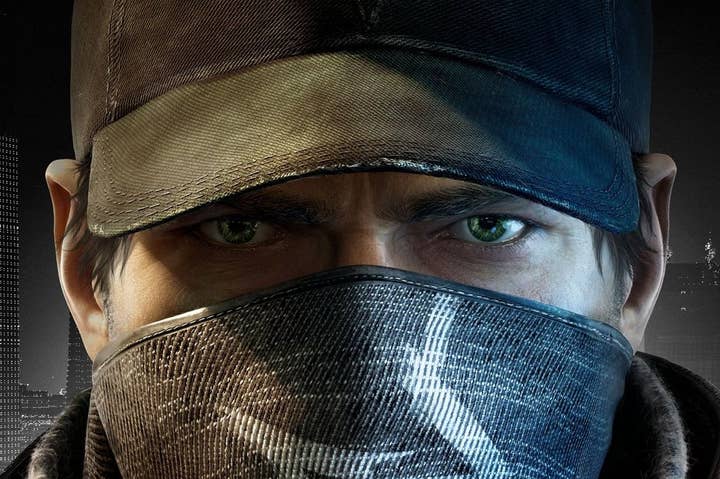

There was something unmistakably Splinter Cell about the way the game's protagonist, Aiden Pearce, could mark and execute his enemies, more than a little Assassin's Creed to the manner in which he traversed the city, and a strong sense of both of those franchises in the importance of climbing towers to unlocking new missions.

"In many ways, Watch Dogs feels like a synthesis of some of publisher Ubisoft's flagship series," Polygon observed in its review of the game, and it wasn't the only outlet to highlight those familiar elements. "Call it Ubisoft's house style, if you like," Eurogamer noted, "but it leaves Watch Dogs feeling more like a greatest hits compilation than a distinct title."

This tendency didn't begin with Watch Dogs. From hunting to crafting to loot, many of Ubisoft's games in the last few years have been underpinned by and structured around a clutch of increasingly familiar mechanics - to the point where they have become a caveat in reviews on websites read by millions of potential customers. At E3, GamesIndustry International had the opportunity to ask Lionel Raynaud, Ubisoft Montreal's vice president of creative, about the trend. And though it might seem counter-intuitive at first, Raynaud argues that the common ground is all in the name of creating a better product.

"The time you spend reinventing something is time you don't have to advance and add something new"

"We need to build on what we have," he says. "While we fight recipes, and we fight the fact that our games could feel similar, the time you spend reinventing something is time you don't have to advance and add something new."

Raynaud is quick to dismiss the idea that these recontextualised ideas are a necessity when making games on such a huge scale, both in terms of the amount of content produced and the hundreds of employees that comprise their development teams - employees who are often working in different studios and even in different countries. There is, Raynaud insists, nothing simple about making a game like Watch Dogs work.

"It's never a case of, 'it's easier to do this.' It's not easier to make a system work in Watch Dogs just because it works in Far Cry. That's still very difficult to do."

However, Eurogamer's somewhat flippant comment about Ubisoft's "house style" may be closer to the mark than the reviewer intended. Raynaud admits that Ubisoft "thinks a lot" about the qualitative risks of having such a wide range of mechanics, missions and other distractions in its AAA games. Making some aspects of that content familiar from other titles is not a specific goal, exactly, but Raynaud sees it as a distinct advantage.

"The true thing that we're aiming at is consistency, and creating an experience that feels natural. So, yes, if a player recognises a system, and we don't need a tutorial for it, that's a good thing. It's a more direct approach to the fun. But every time we iterate we try to make it better, even within the same franchise."

This speaks to the uneasy relationship between innovation and quality. For Raynaud, making each game better than the last is the ultimate goal, and that's more about improving on what has already been established than doing something different every single time. He acknowledges that Ubisoft has to be cautious about the "side effects" of that strategy, but the degree of certainty it does provide is a great platform on which to experiment and explore new ideas.

"The goal is to surprise, with something new and something better," he says. "Everytime we say, 'Yes, it was lovely in Assassin's Creed but we'll do everything different,' it's scary. The chances are we won't offer a better game, and we absolutely want to offer a better game. We invent when we need to invent."